The Eldritch Creation: A monthly article on cult films and great literature

by Treehouse Editors

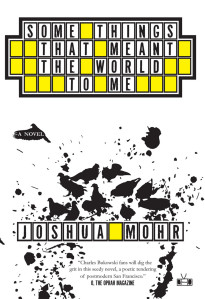

Volume 2: The Science of Sleep and Some Things That Meant the World to Me

by Caleb Andrew Ward

In Michel Gondry’s 2006 film The Science of Sleep, Stéphane’s (Gael Garcia Bernal) transition is seamless from his father’s apartment to the dream world he has created using cardboard and imagination. Stéphane’s line between reality and the dream world becomes increasingly blurred as his innocent obsession with his new neighbor Stéphanie (Charlotte Gainsbourg) reaches a climax. He sleepwalks, creates new worlds, and ignores common social boundaries.

Joshua Mohr’s debut novel Some Things That Meant the World to Me

(2009) was met with much praise. Mohr’s background in the seedy

underbelly of San Francisco’s Mission District gave him great insight

into the world where his whimsical novel is set. Mohr’s work has proved

to be a pace where filth and grime are celebrated as characteristics

that make people more realistic rather than shining them up and putting

them on a pedestal. They are met with trepidation and a chance to be who

they really are. Teaching creative writing at a halfway house in San

Fran, Mohr is able to see how the gritty world the city tries to hide

its seething with beauty and pulchritude. Much of his fiction takes

place in the Mission District.

Joshua Mohr’s debut novel Some Things That Meant the World to Me

(2009) was met with much praise. Mohr’s background in the seedy

underbelly of San Francisco’s Mission District gave him great insight

into the world where his whimsical novel is set. Mohr’s work has proved

to be a pace where filth and grime are celebrated as characteristics

that make people more realistic rather than shining them up and putting

them on a pedestal. They are met with trepidation and a chance to be who

they really are. Teaching creative writing at a halfway house in San

Fran, Mohr is able to see how the gritty world the city tries to hide

its seething with beauty and pulchritude. Much of his fiction takes

place in the Mission District.

Rhonda, a 30-year-old man suffering from depersonalization, wanders San Francisco’s mission district (a common theme in Joshua Mohr’s books) with a broken arm and at night joins his younger self inside a dumpster behind a Mexican food place to travel to his past. The deeper Rhonda goes into his past the more he wants others to believe he has actually found a link between the present and his past. As Stéphane and Rhonda journey deeper into their dormant imaginations they lose their grasp on reality. Stéphane’s relationship with Stéphanie is more real in his dreams than in physical existence and Rhonda at times disregards his relationship with his neighbor Old Lady Rhonda in order to pursue his reconciliation with his mother’s old boyfriend Letch.

Rhonda and Stéphane couldn’t be more different in their personalities. Rhonda is a 30-year-old smoker who gets into fights to save hookers and drinks more than he does speak while Stéphane is a quiet man-child, who builds models, imagines he has his own TV show called “Stéphane TV,” and rarely gets drunk. But while the two are different they are also similar. Where these two reach their catharsis is during the interactions with their female auxiliaries. Old Lady Rhonda is in an abusive domestic situation. She is in a constant daily struggle to fight off her husband and keep him from knowing of the mother-son relationship between herself and Rhonda. Stéphanie could see herself falling in love with Stéphane, but his disconnection between reality and the dream world he has created causes for a negative discourse in their relationship. Rhonda and Stéphane have become too intrinsic and have shut themselves off from the others around them who deeply care for them.

So, who gives a shit? We are the watchers and observers, but also the participants. In films and books like these we immerse ourselves in them eventually walking away feeling jilted or disoriented. The dream-like consciousness achieved in both The Science of Sleep and Some Things That Meant the World to Me creates an experience rather than an entertainment. Gaspar Noé says of film, “Very frequently what a life boils down to is a single, very traumatizing experience.” The experiences both characters luxuriate in are comparative and hellish.

Though The Science of Sleep is a more ambiguous ending than Some Things That Meant the World to Me (we end with a close up of sleeping Stéphane dreaming of a better ending with Stéphanie as his love) the two are close in tone. Stéphane and Rhonda are confused wanderers attempting to navigate the parts of their mind yet untilled. The mind is a dangerous place to plunge too deep and these two protagonists show that. They are vessels for audiences and readers to use for character study. If they can thrust themselves so far into their minds and achieve a sense of purpose then can the same go for us?